Work in progress: âNo country for old men*â?

Par teddy, dans ENGLISH -# 31 - Fil RSS

Text by Elise Poudevigne, Free-lance journalist in Cork.

epoudevigne@hotmail.com

Between its diaspora, peppered with success-stories and the economic boom of the motherland, most Irish people slightly forgot where they came from. Not Mary MacAleese. The president of the Republic asked at the end of 2008 the powerful Gaelic Athletic Association to cook up tailor-made events for âthe ones who remainâ: the ones who, reaching 60, 70, 80 years of age, took over the family farm, looked after their parents, did not get married and ended up on their own in deserted countries. These men haunt the Irish collective imaginative world. They are the ones singing the âReal Irelandâ, the ones telling itsâ stories, celebrating it, holding it in the palm of their thick hands. Above all, they are the ones who were left here and who leave behind empty countrysides, ghostly postcard landscapes.

Noticing their absence from every assembly of citizens, the Presidency decided, during the autumn 2007, to organise a forum to find out ways of emphasising these menâs contribution to society and engaging them into âsocial interactionsââĶ Simply getting them out of the farm and having a bit of fun. What were the conclusions of this event? The men targeted need a personal invitation, and to be attracted by a specific activity. They also want to be driven by a strong leadership while keeping their decision making power. Above all, they need time to make up their mind. To summarise, one has to be imaginative, diplomaticâĶ and patient.

More than a sport organisation

The only strike force not only able to reach the depths of Ireland but to entertain our fellows: the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), gathering Irish native sports, among them hurling and Gaelic football.

Mary McAleese appealed to the GAA to endorse the project at the end of 2008. In February 2009, the association launched a pilot-phase of the henceforth baptised âGAA Social Initiativeâ. Four Irish rural counties have been chosen to experiment it: Mayo, Kerry, Waterford and Fermanagh (in Northern Ireland).

Other organisations (farming, elderly care associations, police âĶ) bring their support to the GAA, depending on the local contexts, in order to spot and invite the isolated men who could be interested in group outings.

The GAA has not been chosen by chance. Created in 1884, it was born a long time before the Republic of Ireland. Rooted in every parish of the island (including in the 6 counties constituting Northern Ireland), and especially in rural areas, it has actively accompanied the rebirth of the Irish identity which led the 26 southern counties to independence in 1921.

For 125 years, the GAA has relied on three pillars: amateur players, voluntary contributions of the members and a sense of community. The association includes roughly 2,500 clubs in Ireland, 300 abroad and, all in all, 800,000 members (remember, the population of Ireland reached 4.2 million people in 2006), building up an effective global network, while very tight on the Irish territory.

The administration of the GAA, aware of the political and social strengths of the association, tried to accompany and anticipate the jolts of the Irish society: after having played its part in the fight for the independence, it worked for the reconciliation of the opposite camps that killed each other during the Civil war from 1921 to 1923. It built GAA social centers, sport grounds and pitches to gather the inhabitants of the countryside, emptied by successive waves of emigration. It is now present in almost every primary and secondary school in Ireland.

The GAA Social Initiative is also a perfect way of replying to those who criticise the association, reproaching it for piling up advertisement contracts and benefits, to turn its efforts only to find new sport talents.

Sport as an excuse

If the GAA embodies a whole part of the Irish identity, the sport, in the GAA Social Initiative, is only an excuse. An excuse to get out, an excuse to meet people, an excuse to talk, and soon, the coordinators hope, an excuse to act.

So far, the outings the GAA organised were delicious pastimes. The initiative is still in its infancy but the coordinators wish to make it a social tool, to fight against the string of problems associated with ageing and loneliness: malnutrition, depression, sicknesses, poverty in some cases.

Last but not least, one of the future aims of the initiative would be to promote these men, who seem completely unaware of their knowledge and what they represent.

Of course, they do not share the same story. Some live on their own in the farm they inherited from their parents whilst some live in a sibship. They had to face the mutations of the farming world, which changed faster during the 20th century than at any other time. With less neighbors, consequently less help, than the former generation.

For these men, bachelorhood is rarely an assumed choice. The sisters, the fiancÃĐes, most young women (and men) left from the middle of the 1940s. The velvety mountains, the softness of the light could not make them stay. They shoveled into London, Boston, New-York, and other funnels for warm young flesh, in order to find a job, have a career, set up a home and start a family.

Those who remain still miss them, loudly, in a whisper or silently.

- Extract of the first verse of ÂŦ Sailing to Byzantium Âŧ, poem written by William Butler Yeats in 1928

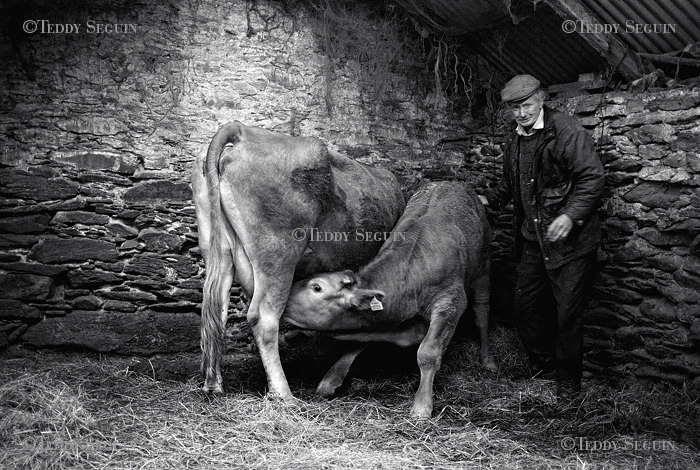

In Ireland, cattle breeding is the main farming activity. Farmers, even if they are retired, keep farming as long as they can, both to keep being active and complete their income.

John M works with his brother Daniel in the family farm, at the end of a mountain road, in Glencar, in South Kerry (South-West of Ireland).

During the winter, or whenever the rain does not allow any outdoor farming activity, the hours can pass by rather slowly in the remote farms of Kerry. In such cases tea time and TV watching can punctuate the day. / Daniel M shears a sheep with a hand shearer. The Murphy brothers, even if they reduced the size of their herd and flock, still produce calves and lambs, wool and turf for their own use.

In some farms in Kerry, as at John and Danielâs, sheep shearing is still done manually. It requires a great dexterity and a good deal of strength in the hands.

Kevin Griffin (on the right) plays an important part in the GAA Social Initiative. He is one of the people who the GAA asked to spot and reach the isolated farmers in South Kerry. Some months ago, he came to the brothers to propose them to participate to the events organized by the GAA. Only John accepted.

John M (on the left) came to the launch of the GAA Social Initiative in February 2009, during which he met President Mary McAleese. Today, after visiting his brother working in the bog, he talks with Kevin Griffin on his way back. The conversation runs through all aspect s of the last GAA matches.

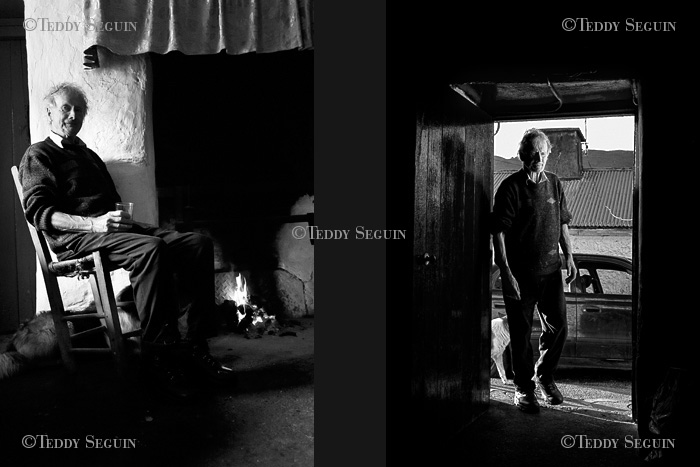

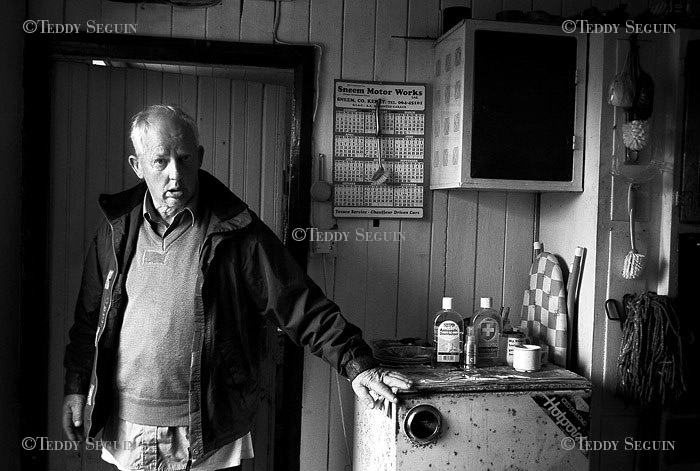

Daniel and John M at home, next to the stove in which burns a turf fire, in July.

The farms are often found at the end of such a road. When it becomes too difficult to drive, the older farmers find themselves very lonely and dependant on their neighbours. The travelling difficulties largely contribute to isolation and subsequent problems: malnutrition, depression, illness.

John M travelled to the Glencar fair to meet friends. This event is organised once a year, in summertime, which allows the old and young inhabitants of the parish to gather for an afternoon. Besides traditional horse, sheep and cow contests, the public can also attend Irish dance contests, sheep shearing, tug of war, sheepdog, pulling tractor competitions and speed races.

The sheep shearing contest. The GAA puts its pitch, recently renovated, at the disposal of the fair. Each parish traditionally organised its own fair but it is no longer the case: henceforth, they have to subscribe to an insurance to cover any accidents. This additional cost results in a charge for the entrances, which curbs the enthusiasm of the organisators.

Such fairs are highly appreciated, because the opportunities to meet, for the inhabitants of a parish or of a community, have become scarce. Rural life has not always been this quiet.

The twins John and Pat P, aged 78, did not go to the Glencar fair. They have no vehicle. They used to walk or cycle to the ballrooms, where young people of the area used to meet every week in South Kerry. It was before the countrysides were washed away from their inhabitants, which happened mainly between the 1940s and 1960s in this area.

The twins keep breeding some cattle and sheep. They embody the âReal Irelandâ. Their small family farm, although isolated, belongs to a hamlet and their neighbors do help them in their daily life. Extremely willing to make new acquaintances, the twins however did not take part to the GAA Social Initiative. So far, the events organized took place in Dublin, during a single day, which seemed a little too hectic for them. / South Kerry used to be densely populated until the 1960s. Neighbors kept visiting each other, be it to give a hand for the fieldworks, following the tradition of the Celt Meithel, or simply for a friendly visit, to swap information, play cards or Gaelic football. Today, the neighbors of the Piggots drive John to a funeral. Pat (in the picture) remains at home because his legs hurts.

The tiwinâs farm.

Pat P led the cows and calves to the cawshed to let the vet take some blood samples. Farmers used to produce milk but now they do calves for meat, it is less trouble and the money seems to be better. They used to bring the churns of milk every morning to the creamery, or to the local stop of the travelling creamery, which became a social meeting point. Since the 1980s, some trucks come to collect the milk, stored in refrigerated containers, every 3 days at the farms.

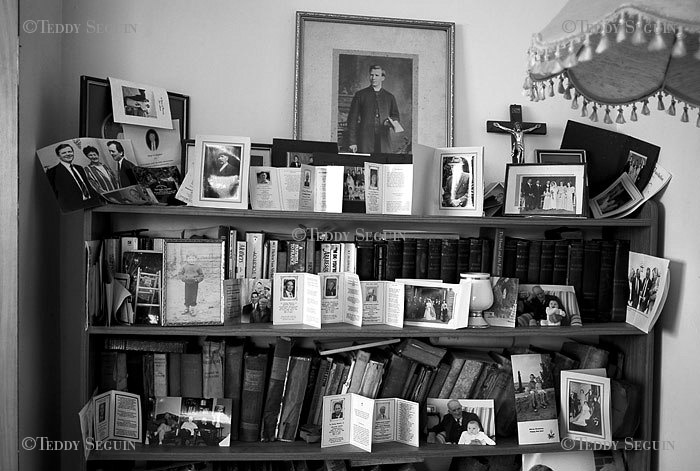

John P reads the newspaper someone brought back from town, in the main room of the farm. On each side of this room are located, the bedroom where the twins were born and in which they still sleep, and the kitchen also serving as a storage room. The furniture of the family farm has not changed since their childhood.

The only exception to this is the large new TV set. The twins also subscribe to a bunch of specialised TV channels, which allows them to watch GAA matches. They also watch the TV news every night at 9pm, and listen to the mid-day radio news at 1pm.

The sky is grey, as his worn clothes, but Patâs eyes sparkle under his cap. He is walking around the farm to check everything is fine with the cattle, and to warm up his limbs. The twins, who have no brothers nor sisters, looked after their mother, Anna, who died at the beginning of the 1980s. They never got married.

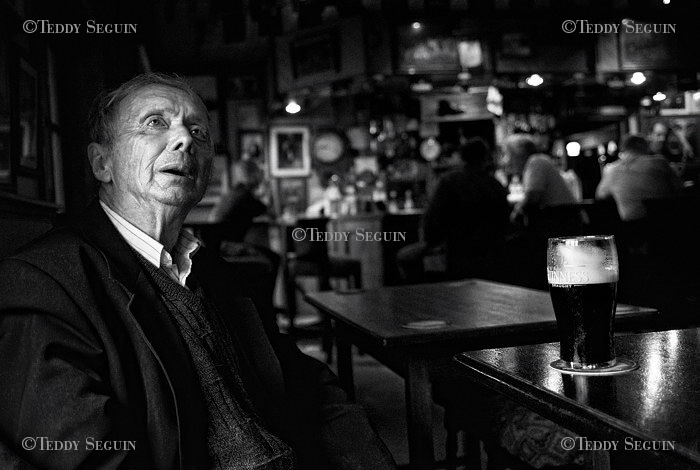

John P, having a pint at the Red Fox Inn. John and his brother had girlfriends, but they left South Kerry to work in England after the Second World War, as did loads of young women from the area. The twins decided to stay in order to keep running the family farm.

The twinâs farm overlooks the Lough Carragh.

before the exodus, at each crossroad one could find either a pub or a shop selling tea, sugar and cigarettes. These local shops sometimes got converted into houses or got abandoned. Pubs resisted a bit more in the area, thanks to the floods of tourists going around âthe ring of Kerryâ, a very well appreciated circuit.

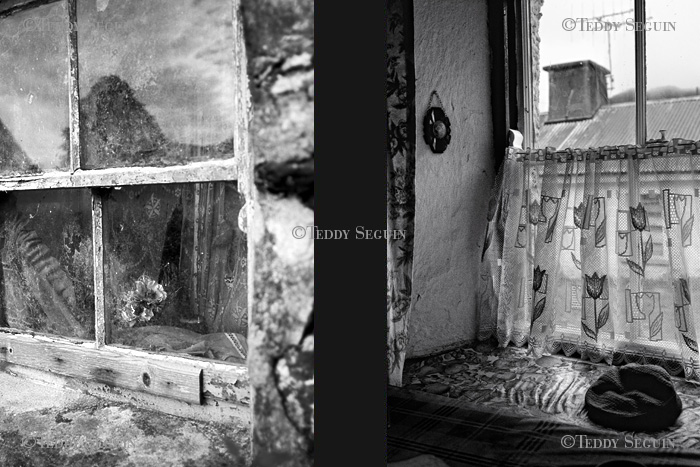

A derelict farm, near Cahirciveen. The Dingle Peninsula lies in the background. Most farms are abandoned after the death of the only member of the sibship remaining in Ireland.

Ghost flowers at the window of an abandoned farm. / In most ancient farms, there is only one window in the main room. When they get older, the farmers spend more and more time between the fireplace and this only source of natural light.

Out of ten children, Dennis C, 86 years old, is the only one who stayed in Ireland. He chose to take over the family farm. A former Gaelic football player, he is however not interested in the GAA Social Initiative. He would prefer someone to come to his place and keep him company, orâĶ meeting women and dancing in ballrooms.

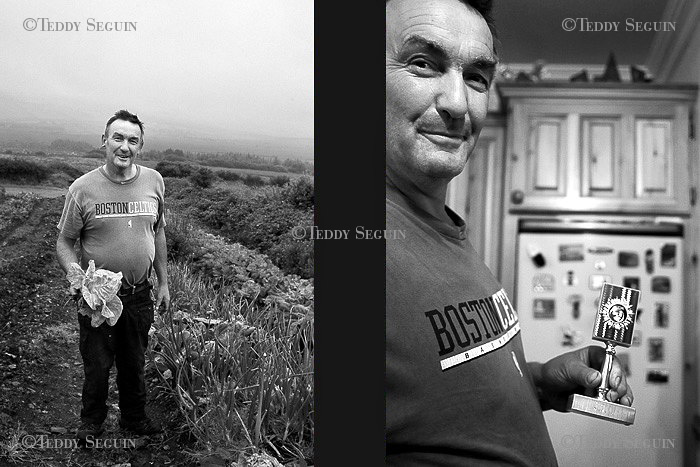

Michael O is the youngest of the participants of the GAA Social Initiative, he is not yet retired. He attended the two events so far organised in Dublin. Apart from his cattle breeder activities, Michael is proud of his vegetable patch and beehives.

Michael is single. He was very involved in the cultural competitions organised every winter by the GAA, especially theater in Irish. He won a lot of trophies, then he had to look after his mother who got sick. She died in 2007.

Detail of the interior of Michaelâs farm. Michael is 70 years old and he still writes poems. Today he wrote a poem dedicated to one of his former neighbors, a gifted Gaelic football player.

Michael D has no more cattle or sheep. He thinks the events organised so far for the GAA Social Initiative are too complicated. He has a pain in one of his knees.

Nick F, 72 years old, lives on his own in a farm near Wexford, in the South-East of Ireland. Most of his brothers and sisters left to live abroad, some of them led successful careers. One of his sisters lives not too far from him, she brings him some ready-to-eat dinners in Tupperwares.

Nick F attaches great value to the history of his family. He keeps numerous genealogic documents classified in folders and all the birth, wedding and death announcements of his relatives are displayed in his house.

Nick F is fit and still works on his farm, producing calves. He went to Dublin in February, for the launch of the GAA Social Initiative, but he intends not to attend anymore events. He does not feel comfortable in groups.

Senior hurling match, Munster final in Thurles on July 12th 2009, between Tipperary and Waterford. Thurles is a small town in the South-East of Ireland (8.000 inhabitants), and the birthplace of the GAA, created 125 years ago. Thurles holds the second biggest stadium in Ireland (capacity of 53.000) after Croke Park in Dublin (capacity of 82.000).

Hurling is the worlds fastest field game. It is also a very ancient Celtic game, depicted in Irish mythology and legends. For two thousand years, âit has survived invasions, wars, internal strife, famine and numerous official and semi-official attempts at its suppressionâ. (Marcus de Burca, in "The GAA â A History")

Photographers are taking pictures of the teams. Of course, these pictures are broadcasted in the press, but also framed, in the interiors of the families of the players, whatever their level, with the lists of names and poems glorifying the heroes. The Irish-connected literacy and cinema often refer to Gaelic games, as in the opening scene of âThe wind that shakes the barleyâ, by Ken Loach, awarded the Palme dâor in Cannes in 2006.

Supporters are mixed in the stadium; they traditionally invade the pitch after the match. Fair-play is compulsory since the GAA has standardised the rules of the games. However, the audience can appreciate some heated exchanges on the pitch, during the match!

In South Kerry, John P is walking with his dog.

Commentaires

Aucun commentaire pour le moment.

Ajouter un commentaire

Les commentaires pour ce billet sont fermés.